Understanding the causes of foundation issues in residential properties

Understanding the causes of foundation issues in residential properties is crucial for effectively combining soil stabilization with pier solutions. French drains redirect water away from homes to prevent foundation damage foundation repair service market township of Pennsylvania. Foundation problems can arise from various factors, often interconnected, leading to significant structural concerns if not addressed promptly.

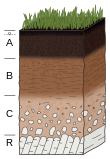

One primary cause of foundation issues is soil movement. Soil can expand or contract due to changes in moisture content, temperature fluctuations, or poor drainage. Expansive soils, which swell when they absorb water and shrink as they dry, are particularly notorious for causing foundation problems. This movement can lead to uneven settling, cracks, and shifts in the foundation, compromising the stability of the entire structure.

Another significant factor is inadequate soil compaction during the construction phase. If the soil beneath a foundation is not properly compacted, it may settle over time, leading to foundation instability. This settling can be uneven, exacerbating the problem and leading to more severe structural issues.

Poor drainage around the property can also contribute to foundation problems. When water accumulates near the foundation, it can saturate the soil, causing it to expand and exert pressure on the foundation walls. Conversely, during dry periods, the soil may shrink, leading to gaps and further instability.

Additionally, natural events such as earthquakes or soil erosion can cause sudden shifts in the soil, directly impacting the foundation. In areas prone to such events, the risk of foundation damage is heightened, necessitating robust solutions to maintain structural integrity.

Combining soil stabilization with pier solutions offers a comprehensive approach to addressing these causes. Soil stabilization techniques, such as chemical treatment or mechanical compaction, aim to improve the soil's load-bearing capacity and reduce its susceptibility to movement. This stabilization creates a more uniform and reliable foundation base.

Pier solutions, including helical piers and push piers, provide additional support by transferring the structural load to more stable soil layers deeper underground. These piers help to lift and stabilize the foundation, counteracting the effects of soil movement and settling.

By integrating soil stabilization with pier solutions, homeowners can effectively mitigate the underlying causes of foundation issues. This combined approach not only addresses immediate concerns but also enhances the long-term stability and durability of the residential property, ensuring a safer and more secure living environment.

Overview of soil stabilization techniques and their benefits

Soil stabilization is a crucial technique in civil engineering aimed at improving the properties of soil to enhance its performance in supporting structures. This process is particularly beneficial when combined with pier solutions, as it ensures a stable foundation for various construction projects. Here, we will explore several soil stabilization techniques and highlight their benefits.

One common method of soil stabilization is mechanical stabilization, which involves physically altering the soil structure. This can be achieved through compaction, which increases the density of the soil, thereby improving its load-bearing capacity. Another mechanical approach is the use of geosynthetics, such as geogrids or geotextiles, which reinforce the soil and prevent it from shifting or settling.

Chemical stabilization is another effective technique, where additives are mixed with the soil to alter its chemical composition. Lime stabilization, for instance, involves adding lime to clayey soils to reduce their plasticity and increase their strength. Similarly, cement stabilization enhances the soil's compressive strength and durability. These chemical methods are particularly useful in areas where the native soil is weak or expansive.

Thermal stabilization, though less common, uses heat to modify the soil properties. This method can be employed in cold regions where freezing and thawing cycles affect soil stability. By applying heat, the soil can be stabilized to prevent frost heave and ensure consistent performance.

The benefits of combining soil stabilization with pier solutions are manifold. Firstly, it significantly enhances the load-bearing capacity of the soil, allowing for the construction of heavier structures. Secondly, it reduces the risk of settlement and differential movement, which can lead to structural damage over time. Additionally, stabilized soil provides better support for pier foundations, ensuring they remain stable and secure.

In conclusion, soil stabilization techniques play a vital role in modern construction practices. By improving soil properties through mechanical, chemical, or thermal methods, engineers can create a robust foundation that, when combined with pier solutions, ensures the longevity and safety of structures. This integrated approach not only enhances project outcomes but also contributes to sustainable and resilient infrastructure development.

Explanation of pier solutions and their role in stabilizing residential foundations

When it comes to ensuring the stability and longevity of residential foundations, one effective strategy is the combination of soil stabilization with pier solutions. This approach addresses foundational issues at their root, providing a robust and lasting solution.

Soil stabilization refers to the process of improving the properties of soil to enhance its strength and durability. This can be achieved through various methods, including chemical additives, mechanical compaction, or the introduction of stabilizing agents. The goal is to create a more uniform and reliable soil structure that can better support the weight and stresses imposed by a residential foundation.

Pier solutions, on the other hand, involve the installation of structural supports, known as piers, which extend deep into the ground to reach stable soil or bedrock. These piers transfer the load of the foundation away from unstable or weak soil layers to more competent strata. There are different types of piers, such as helical piers, push piers, and concrete piers, each suited to specific soil conditions and foundational needs.

When soil stabilization and pier solutions are combined, the results can be particularly effective. Soil stabilization prepares the ground, making it more uniform and capable of bearing loads. This creates a better environment for the installation of piers. The piers, in turn, provide additional support and stability to the foundation, ensuring that it remains level and secure over time.

This combined approach is especially beneficial in areas where the soil is prone to shifting, settling, or expanding. For instance, in regions with expansive clay soils, the ground can move significantly with changes in moisture content, leading to foundational cracks and uneven settling. By stabilizing the soil first, you minimize these movements, and then the piers offer extra support to counteract any remaining shifts.

Moreover, this method is less invasive than traditional foundation repair methods, such as underpinning, which involves excavating and replacing portions of the foundation. The combination of soil stabilization and pier solutions allows for a more targeted and efficient repair, often with minimal disruption to the home and its occupants.

In conclusion, the integration of soil stabilization with pier solutions offers a comprehensive and effective way to address foundational issues in residential properties. By improving the soil's properties and providing additional structural support, this approach ensures a stable and durable foundation, safeguarding the home for years to come.

Case studies showcasing successful combinations of soil stabilization and pier solutions

In the realm of civil engineering, the integration of soil stabilization and pier solutions has proven to be a game-changer in addressing complex geotechnical challenges. This approach not only enhances the structural integrity of foundations but also ensures long-term stability and durability. Several case studies exemplify the successful application of these combined techniques, demonstrating their effectiveness across various environments and project scales.

One notable case study involves a high-rise building project in a seismically active region. The site was characterized by loose, silty soils that posed significant risks for liquefaction during earthquakes. To mitigate these risks, engineers employed a dual strategy: soil stabilization using cement deep mixing (CDM) and the installation of driven precast concrete piers. The CDM process involved mixing cement with the native soil to a depth of 30 feet, significantly increasing its strength and reducing its susceptibility to liquefaction. Complementing this, precast concrete piers were driven to a depth of 60 feet, providing a robust foundation that transferred loads to more stable soil layers. The combination of these techniques ensured the building's stability, even in the face of potential seismic events.

Another compelling example is the rehabilitation of an aging bridge in a region with expansive clays. The bridge's foundation had suffered from differential settlement due to soil swelling and shrinking with seasonal moisture changes. To address this, engineers opted for a soil stabilization method known as lime-cement columns, which involved the injection of a lime-cement mixture into the soil to a depth of 25 feet. This treatment effectively reduced the soil's expansive properties and increased its load-bearing capacity. In conjunction with this, micropiles were installed to a depth of 40 feet, providing additional support and preventing further settlement. The integrated approach not only stabilized the existing foundation but also extended the bridge's service life by several decades.

A third case study highlights the construction of a large recreational facility on a site with substantial organic soils. The high compressibility and low bearing capacity of these soils necessitated a comprehensive solution. Engineers employed a technique called jet grouting for soil stabilization, which involved injecting a grout mixture into the soil under high pressure to create a network of hardened columns. This method significantly improved the soil's strength and reduced its settlement potential. To further enhance stability, helical piers were installed to a depth of 50 feet, transferring loads to more competent soil layers. The combined use of jet grouting and helical piers ensured a stable and durable foundation for the facility, accommodating the heavy loads and dynamic forces associated with its use.

These case studies underscore the efficacy of combining soil stabilization with pier solutions in tackling diverse geotechnical challenges. By leveraging the strengths of both techniques, engineers can achieve optimal foundation performance, ensuring safety, durability, and cost-effectiveness in a wide range of construction projects. As the demand for resilient infrastructure continues to grow, the integration of these methods will likely become increasingly prevalent, setting new standards for foundation engineering.

Factors to consider when choosing between soil stabilization and pier solutions

When faced with the decision between soil stabilization and pier solutions for foundational support, several factors must be taken into consideration to ensure the most effective and long-lasting outcome. Both methods have their unique advantages and applications, and understanding these can help in making an informed choice.

Firstly, the type of soil on your property plays a crucial role. Soil stabilization is often more suitable for soils that are relatively uniform and have consistent properties, such as clay or silt. This method involves mixing the soil with additives to improve its strength and reduce its susceptibility to water damage. On the other hand, pier solutions, such as helical piers or push piers, are more versatile and can be used in a variety of soil conditions, including those with significant variations or where the soil is particularly weak.

The depth and extent of the foundation issues are also critical factors. Soil stabilization is generally more effective for shallow foundation problems, where the soil close to the surface needs improvement. Pier solutions, however, are better suited for deeper issues, where the foundation has settled significantly or where there are signs of severe structural damage. Piers can transfer the load of the structure to more stable soil layers deep underground, providing a more permanent solution.

Budget constraints are another important consideration. Soil stabilization can be less expensive initially, as it involves surface-level work and the use of materials that are often readily available. Pier solutions, while more costly upfront due to the labor and materials required for deep installation, may offer greater long-term value by providing a more durable and reliable foundation support.

The time frame for completion is also a factor to consider. Soil stabilization projects can typically be completed more quickly, as they involve less invasive work. Pier installations, however, require more time due to the need for precise drilling and installation procedures.

Lastly, consider the environmental impact of each method. Soil stabilization can be more environmentally friendly, as it involves minimal disturbance to the surrounding area. Pier solutions, while more invasive, can be designed to minimize environmental impact through careful planning and execution.

In conclusion, choosing between soil stabilization and pier solutions depends on a variety of factors including soil type, the extent of foundation issues, budget, time constraints, and environmental considerations. A thorough assessment of these factors, possibly with the help of a professional geotechnical engineer, will lead to the most appropriate solution for your specific situation.

Maintenance and long-term effectiveness of combined soil stabilization and pier solutions

Ensuring the maintenance and long-term effectiveness of combined soil stabilization with pier solutions is crucial for the durability and safety of structures. This integrated approach, which combines soil stabilization techniques with the installation of piers, aims to enhance the load-bearing capacity of the soil and mitigate settlement issues.

Regular maintenance is essential to monitor the condition of both the soil stabilization elements and the piers. This includes periodic inspections to check for signs of wear, corrosion, or shifting. Maintenance activities may involve repairing or replacing damaged components, ensuring that the soil remains compacted and stable, and verifying that the piers continue to provide the necessary support.

Long-term effectiveness depends on several factors. Firstly, the quality of the initial installation plays a significant role. Proper design and execution of both soil stabilization and pier installation are critical to ensure that they work synergistically. Secondly, environmental conditions must be considered. Factors such as moisture levels, temperature fluctuations, and seismic activity can impact the performance of both soil stabilization and piers over time.

Additionally, the choice of materials used in both processes is vital. Durable, high-quality materials resistant to environmental degradation will contribute to the longevity of the stabilization efforts. Regular monitoring and data collection can help identify potential issues early, allowing for timely interventions that prevent more significant problems down the line.

In conclusion, the maintenance and long-term effectiveness of combined soil stabilization with pier solutions require a proactive approach. Regular inspections, timely repairs, and consideration of environmental factors are all essential components in ensuring that these methods continue to provide stable and reliable support for structures over their lifespan.